Bruce Lee random walk

Julia编程(一): 入门

想通过短篇幅的一篇文章将一种语言讲全讲透是很难的,因此这里我将跳过大多数语言共有的特性和元素,着重讲述Julia独有的一些性质。本文是Julia编程系列的第一篇文章,后面将不定期推出Julia的后续教程,着重讲述它在通用计算1,金融分析,高性能计算2, 数值计算3,数据科学4, 5,机器学习,深度学习等方面的应用。

1 引言

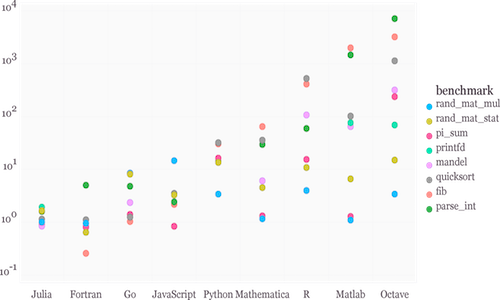

现代语言设计和编译技术能够尽量消除性能妥协,提供一种单一的高产出、高效的环境来构建原型并部署高性能的应用。Julia 语言正扮演着这种角色,它是一种灵活的动态编程语言,非常适用于科学计算和数值计算,并且性能和传统静态类型的语言相当。

Julia编译器不同于Python,R这类语言中使用的解释器。如果我们理解Julia的工作原理,我们将很容易写出接近于C语言速度的代码。

Julia提供了可选类型和多指派等特性,利用类型推断和LLVM实现的即时编译(Just-In-Time)技术来达到高性能,并结合了过程式、函数式和面向对象编程的多种特性。Julia,同R、MATLAB、Python等语言一样,为高级数值计算提供了简易操作和丰富的表达能力,同时还支持泛化编程。为此,Julia构建在数学语言之上,并借鉴了Lisp,Perl,Python,Lua,Ruby等动态语言特性。

- 极小的内核部分。标准库采用Julia自身编写,包括整数运算等最基本的操作

- 是一种丰富的类型语言,可用于构造对象,描述对象,同时可用于类型声明

- 通过多指派(multi-dispatch)在不同参数类型组合上来定义函数行为

- 不同参数类型代码的自动生成

- 高性能,可以达到C一类的静态编译语言的性能

在大多数动态语言中没有类型声明,因此人们不能向编译器指明参数类型,也不能对类型本身进行操作。另一方面,在静态语言中,通常必须向编译器声明类型,类型只存在于编译时,而在运行时无法操纵。在Julia语言中,类型本身就是运行时对象,同时可以将信息传送给编译器。

类型和多指派是统一于Julia的内核特性:函数定义在参数类型的不同组合上,并通过指派来应用。这与数学语言相匹配,因为传统面向对象指派中的第一个参数是很不自然的。算符仅仅是一类特殊标记的函数。

由于运行时类型推断和对性能的持续关注,Julia计算上的性能远超其它动态语言,甚至与静态编译语言不相上下。我们知道,对于大规模数值计算问题,速度一直,并且可能持续,是最关键的考虑标准:过去几十年,用于处理的数据量已经很轻松地赶上了摩尔定律。

Julia语言的目的是将易用性、能力和高效性融合在一种语言中,除此之外,Julia还包含一些重要的优势:

-

免费开源(MIT许可证)

-

用户定义的类型与内置类型一样的紧凑迅捷

-

去向量化

-

并行计算,分布式计算

-

轻量线程(协程coroutines)

-

类型系统

-

数值类型和其它类型之间的转换以及类型晋升

-

UTF-8等Unicode支持

-

直接调用C函数,无须封装或API

-

类shell操作

-

类Lisp宏,元编程(metaprogramming)

2 安装

2.1 REPL(read-eval-print-loop)

- 我们可以直接从官网下载对应的预编译二进制文件或者从源码编译安装

打开方式:

-

直接点击桌面图标打开

-

将julia安装路径添加到.bash_profile文件中,然后可以在Terminal直接输入julia进入开发环境

julia

退出方式:

- ^D

- quit()

搜索模式:

- ^R: reverse

- ^S: forward

shell模式:

julia> ;

shell>

help模式:

julia> ?

help>

中断/取消:

- ^C

清除控制台屏幕:

- ^L

2.2 IJulia notebook

2.3 Juno

2.4 JuliaPro

2.5 Atom/Sublime中安装插件

3 代码执行

3.1 终端输入

julia script.jl arg1 arg2 ...

3.2 Julia环境下

reload("module")

include("test.jl")

4 变量

4.1 UTF-8编码: 如\pi-tab, \delta-tab, \alpha-tab-\hat-tab-\_2-tab

δ = 0.00001

4.2 命名:除了内置语句中保留的关键字外

4.3 风格习惯

- 小写;多个词可以挤在一起

- 词分隔用下划线_表示概念组合或者为了可读性(不鼓励使用)

- 类型名和模块名开始于大写字母,词分隔采用驼峰法

- 函数名和宏名采用无下划线的小写形式

- 有实参的函数可以以!结尾,这些被称为可变(in-place)函数

4.4 作用域(scope)

global

用于module, baremodule, at interactive prompt (REPL)中

local

- soft:用于for, while, comprehensions, try-catch-finally, let

特殊情况:下面将作用域范围从local变成global是错误的

let

local x = 2

let

global x = 3

end

end

- hard:用于函数(如syntax, anonymous & do-blocks), type, immutable, macro

嵌套函数会改变母函数作用域中的local变量

x, y = 1, 2

function foo()

x = 2 # introduces a new local

function bar()

x = 10 # modifies the parent's x

return x+y # y is global

end

return bar() + x # 12 + 10 (x is modified in call of bar())

end

foo() # => 22

这样做的好处同样适用于闭包(closure)

let

state = 0

global counter

counter() = state += 1

end

counter() # => 1

counter() # => 2

while-loop中变量i存储在同一位置,每次迭代都会重用变量

Fs = Array{Any}(2)

i=1

while i <= 2

Fs[i] = ()->i

i += 1

end

Fs[1]() # => 3

Fs[2]() # => 3

let x = x对于不同的x变量存储在不同的位置

Fs = Array{Any}(2)

i=1

while i <= 2

let i = i

Fs[i] = ()->i

end

i += 1

end

Fs[1]() # => 1

Fs[2]() # => 2

for-loop中每次迭代,新的变量存储都会刷新

Fs = Array{Any}(2)

for i = 1:2

Fs[i] = ()->i

end

Fs[1]() # => 1

Fs[2]() # => 2

但是for-loop中会重用已经存在的变量

i = 0

for i = 1:3

end

i # => 3

comprehension(列表推导)每次都会刷新变量地址分配

x = 0

[x for x = 1:3]

x # => 0

const

常量声明适用于全局和局部范围,对于全局范围特别有用。编译器很难优化包含全局变量的代码,因为全局变量的值甚至类型经常会发生改变。因此,如果全局变量不会改变,那么我们添加const声明来提高性能。而编译器能够自动确定局部变量中的常量。

4.5 环境变量

- JULIA_HOME

- JULIA_LOAD_PATH

- JULIA_PKGDIR

- JULIA_HISTORY

- JULIA_SHELL

- JULIA_EDITOR

- JULIA_CPU_CORES

- JULIA_WORKER_TIMEOUT

- JULIA_NUM_THREADS

- JULIA_THREAD_SLEEP_THRESHOLD

- JULIA_EXCLUSIVE

- JULIA_ERROR_COLOR

- JULIA_WARN_COLOR

- JULIA_INFO_COLOR

- JULIA_INPUT_COLOR

- JULIA_ANSWER_COLOR

- JULIA_STACKFRAME_LINEINFO_COLOR

- JULIA_STACKFRAME_FUNCTION_COLOR

- JULIA_GC_ALLOC_POOL

- JULIA_GC_ALLOC_OTHER

- JULIA_GC_ALLOC_PRINT

- JULIA_GC_NO_GENERATIONAL

- JULIA_GC_WAIT_FOR_DEBUGGER

- ENABLE_JITPROFILING

- JULIA_LLVM_ARGS

- JULIA_DEBUG_LOADING

5 数值

5.1 类型

- 整数类型

- Int8, UInt8, Int16, UInt16, Int32, UInt32, Int64, UInt64, Int18, UInt128, Bool(8位)

- 无符号整型是以0x前缀的16进制数0-9a-f

- 当然二进制(0b)和8进制(0o)也是支持的

- 浮点数类型

- IEEE754

- Float16(半精度), Float32(单精度), Float64(双精度)

- 16进制对于浮点数也是有效的,但输出只是Float64

- 浮点数有两个零,分别是0.0和-0.0

- 特殊值

- Inf16, -Inf16, NaN16

- Inf32, -Inf32, NaN32

- Inf, -Inf, NaN

-

复数

c = 1 + 2im real(c) imag(c) conj(c) abs(c) # c到0的距离 abs2(c) angle(c) # 以弧度形式返回相角 a = 1; b = 2; complex(a, b) -

有理数

a = 2; b = 3; num(a // b) numerator(a//b) den(a // b) denominator(a//b) float(a // b)

5.2 操作符

- 位运算

- 非~,与&, 或|, 异或⊻(xor), 逻辑右移>>>, 算术右移>>, 逻辑/算术左移<<

- 数值比较

- ==, !=或者≠, <, <=或者≤, >, >=或者≥

5.3 函数

-

Sys.WORD_SIZE:返回操作系统的位数

-

typeof: 参数是具体数值

-

typemin, typemax: 参数是值类型

-

BigInt, BigFloat: 输入是上一条函数输出

-

sizeof:参数是具体数值

-

eps: 参数是类型或数值

-

zero, one: 参数是类型或数值

-

isa

x = 1 isa(x, Int) -

prevfloat, nextfloat:参数是具体数值

-

setrounding: 参数是类型,选项是RoundUp, RoundDown, RoundNearest

x = 1.1; y = 0.1; setrounding(Float64, RoundDown) do x + y end -

parse: 参数是可转化为数值的抽象字符串,输出是对应数值

-

factorial:阶乘

- 比较函数:

- isequal, isfinite, isinf, isnan

-

setprecision

- 舍入操作

- round(x), round(T, x)

- floor(x), floor(T, x)

- ceil(x), ceil(T, x)

- trunc(x), trunc(T, x)

- 除法

- div, fld, cld, rem, mod, mod1, mod2pi, divrem, fldmod, gcd(x, y…), lcm(x, y…)

-

按元操作:

x = [1, 2, 3, 4] sin.(x) - 三角函数

- sinpi(x), cospi(x): 精确计算sin(pi*x), cos(pi*x)

- atan2: 计算x轴与指定参数点之间的弧度

- sind(x): x以度数给定

- 指数函数

- 平方根sqrt, 立方根cbrt, 直角三角形弦长hypot(x, y)

- 当x接近0时exp(x) - 1的值,expm1(x)

- 当x接近0时log(1 + x)的值,log1p(x)

-

特殊函数: 在Julia0.6以后,特殊函数放在SpecialFunctions包中,需要安装

Pkg.add("SpecialFunctions") using SpecialFunctions - erf, erfc: erfc是erf补函数

- digamma:对数gamma函数lgamma的导数

- airy(z), airy(1, z), airy(2, z), airy(3, z), airy(k, z)

5.4 类型晋升(promotion)

晋升类型

- 内置算术类型和算符的自动晋升:中缀表达式;C,Java,Perl,Python

- 非自动晋升:Ada,ML,Julia;Julia函数需要通过指派和类型系统来实现这样的功能

转换(conversion)

convert(type, value)

在Julia中,我们不能使用convert函数直接将字符串转换成数值类型,即使该字符串可以表示成有效的数值;Julia提供了parse函数来进行这样的操作。

晋升

晋升就是将混合类型的值转换成同一类型。但是,这不同于面向对象的超类型/子类型。

promote(tuple) # => tuple of the same number of values

Rational(n :: Integer, d :: Integer) = Rational(promote(n, d)...)

promote_rule(::Type{Float64}, ::Type{Float32} ) = Float64

promote_type(Int8, UInt16) # => Int64

晋升过程中promote_rule函数蕴含了对称性,因此我们不需要同时定义promote_rule(::Type{A}, ::Type{B})和promote_rule(::Type{B}, ::Type{A})。

5.5 类数学表达式

x = 3

2x^2 - 3x + 1

2^2x

(x - 1)x

(x - 1)(x + 1) # wrong

x(x + 1) # wrong

6 字符串

6.1 Char:类似C和Java,在Julia中Char作为最高等级的类型

-

32位

x = 'x' typeof(x) Int('x') # output: 120 Char(120) # output: 'x' -

Unicode字符包括\u后面至多四位16进制数或\U后面至多八位16进制数

-

并非每个整数都是合法的Unicode编码,合法的Unicode编码包括U+00~U+d7ff,U+e000~U+10ffff

Char(0x110000) isvalid(Char, 0x110000)

6.2 String: 在Julia0.6之前,采用AbstractString

-

不可变

-

偏函数:从索引到字符的映射

-

不同于Python,Julia第一个索引从1开始,最后一个索引可以用end表示,end可以参与运算

str = "Hello, World!\n" str[1] str[end] str[end - 1] str[end÷2] -

索引结果是字符,切片结果是字符串

str[6] str[6:6] -

并非所有索引都有效, 我们用nextind(s, 1), nextind(s, 4)来计算下标

s = "\u2200 x \u2203 y" s[1] s[2] # wrong s[4] -

length(s)<=endof(s)=sizeof(s),所以我们采用如下方式高效迭代字符串

for c in s println(c) end -

字符串插入

a = "Hello" b = "World" string(a, ", ", b, "!\n") "$a, $b!\n" "1 + 2 = $(1 + 2)" - 特殊字符串

- VERSION:遵从一定的命名规则,即主版本号(major version),次版本号(minor version),补丁版本号(patch version),预发布(pre-release),编译环境(build)

v"0.2.1-rc1+win64" typeof(VERSION) # VersionNumber- 字节数组

b"DATA\xff\u2200" - 常见函数

- search(string, char)

- search(string, char, offset)

- contains(string, substring)

- in()

- start(string)

- next(string, index)

- repeat(string, number)

- join(string-array, “, “, “ and “)

- ind2chr(string, index)

- chr2ind(string, index)

7 Unicode

请查阅Julia官方在线文档

8 正则表达式(Regular expressions, regexes)

在Julia中,正则表达式使用以r为前缀的非标准字符串来表示,即它是一种特殊的字符串。正则表达式用于寻找字符串中的正则模式;并且,正则表达式自身也是字符串,它可以被解析成状态机(state machine)来高效搜索字串中的模式。

示例

regex = r"^\s*(?:#|$)"

函数

typeof(regex) # Regex

ismatch(r"^\s*(?:#|$)", "not a comment") # false

ismatch(r"^\s*(?:#|$)", "# a comment") # true

match(r"^\s*(?:#|$)", "not a comment") # nothing

match(r"^\s*(?:#|$)", "# a comment") # RegexMatch("#")

m = match(r"^\s*(?:#\s*(.*?)\s*$|$)", "# a comment ") # RegexMatch("# a comment ", 1="a comment")

m = match(r"[0-9]","aaaa1aaaa2aaaa3",6) # RegexMatch("2")

方法

m = match(r"(a|b)(c)?(d)", "acd")

m.match

m.captures

m.offset

m.offsets # this method has a zero offset

索引

m=match(r"(?<hour>\d+):(?<minute>\d+)","12:45")

m[:minute]

m[2]

替换

replace("first second", r"(\w+) (?<agroup>\w+)", s"\g<agroup> \1")

replace("a", r".", s"\g<0>1")

9 列表/集合/元组/字典/枚举

9.1 列表

Julia中没有专门的List类型,代之以数组类型Array或者用[]生成

9.2 集合

- Set([itr])

Set([1.0, 2.0])

9.3 元组

- Tuple

tuple(1, 'a', pi)

9.4 字典

- Dict([itr])

- Dict{K, V}()

Dict([("A", 1), ("B", 2)])

Dict("A"=>1, "B"=>2)

9.5 枚举

-

enumerate: @enum(name, value1, value2, …)

@enum(Fruit, Banana=1, Apple, Pear)

10 多维数组

一般来说不同于其它科学计算语言,为了性能考虑,Julia不希望程序被写成向量化风格。Julia编译器使用类型推理(type inference),生成标量数组索引的优化代码,使得程序能够被写成占有较少内存的通俗可读的风格而不牺牲性能。

Julia中,函数参量都是引用传递。一些科学计算语言的数组是值传递。在Julia中,对函数内输入数组的修改是对父函数可见的,因此,如果想要展示相似行为,我们应该考虑创建输入的副本。

10.1 数组

基本函数

- eltype(A)

- length(A)

- ndims(A)

- size(A)

- size(A, n)

- indices(A)

- indices(A, n)

- eachindex(A)

- stride(A, k)

- strides(A)

构造&初始化

- Array{T}(dims…)

- zeros(T, dims…)

- zeros(A)

- ones(T, dims…)

- ones(A)

- trues(dims…)

- trues(A)

- falses(dims…)

- falses(A)

- reshape(A, dims…)

- copy(A)

- deepcopy(A)

- similar(A, T, dims…)

- reinterpret(T, A)

- rand(T, dims…)

- randn(T, dims…)

- eye(T, n)

- eye(T, m, n)

- linspace(start, stop, n)

- fill!(A, x)

- fill(x, dims…)

- [A, B, C, …]

连接

- cat(k, A…)

- vcat(A…): cat(1, A…), [A; B; C; …]

- hcat(A…): cat(2, A…), [A B C …], [A B; C D; …]

带类型的初始化

- T[A, B, C, …]

列表推导

- A = [F(x,y,…) for x=rx, y=ry, …]

- A = T[F(x,y,…) for x=rx, y=ry, …]

[(i,j) for i=1:3 for j=1:i if i+j == 4]

生成器(generator): 按需迭代产生值,不需要分配数组并提前存储

map(tuple, (1/(i+j) for i=1:2, j=1:2), [1 3; 2 4])

索引

- 下标: X = getindex(A, I_1, I_2, …, I_n)

- 逻辑索引,即掩码(mask): find(B)

- searchsorted(A, value)

- setindex!(A, X, I_1, I_2, …, I_n)

x = reshape(1:16, 4, 4)

# x = collect(reshape(1:16, 4, 4))

x[2:3, 2:end-1]

x[map(ispow2, x)]

x[1, [2 3; 4 1]]

迭代

- 按元

- 下标:如果数组类型是可以快速线性索引的(fast linear indexing),那么下标为Int,否则下标为

CartesianIndex

for a in A

# Do something with the element a

end

for i in eachindex(A)

# Do something with i and/or A[i]

end

A = rand(4,3)

B = view(A, 1:3, 2:3)

for i in eachindex(B)

@show i

end

向量化算符&函数

算符:

- 单元:-, +, !

- 二元:+, -, *, .*, /, ./, \, .\, ^, .^, div, mod

- 比较:.==, .!=, .<, .<=, .>, .>=

- 单元Boolean/按位:~

- 二元Boolean/按位:&, |, ⊻

函数:

- abs abs2 angle cbrt airy airyai airyaiprime airybi airybiprime airyprime acos acosh asin asinh atan atan2 atanh acsc acsch asec asech acot acoth cos cospi cosh sin sinpi sinh tan tanh sinc cosc csc csch sec sech cot coth acosd asind atand asecd acscd acotd cosd sind tand secd cscd cotd besselh besseli besselj besselj0 besselj1 besselk bessely bessely0 bessely1 exp erf erfc erfinv erfcinv exp2 expm1 beta dawson digamma erfcx erfi exponent eta zeta gamma hankelh1 hankelh2 ceil floor round trunc isfinite isinf isnan lbeta lfact lgamma log log10 log1p log2 copysign max min significand sqrt hypot

自动向量化:

- @vectorize_1arg type func

- @vectorize_2arg type func

广播

- repmat

- broadcast, broadcast!

10.2 稀疏矩阵

包含足够的零,以特殊的数据结构存储,节省了空间和时间。

压缩稀疏列(compressed sparse column, CSC)存储

- 便利的按列访问

- 按行访问相当慢

- nnz()

-

countnz()

struct SparseMatrixCSC{Tv,Ti<:Integer} <: AbstractSparseMatrix{Tv,Ti} m::Int # Number of rows n::Int # Number of columns colptr::Vector{Ti} # Column i is in colptr[i]:(colptr[i+1]-1) rowval::Vector{Ti} # Row indices of stored values nzval::Vector{Tv} # Stored values, typically nonzeros end

构造器

稀疏矩阵构造:

- spzeros(m, n)

- spones(S)

- speye(n)

- sparse(A)

- issparse(A)

- sprand(m, n, d)

- sprandn(m, n, d)

- sprandn(m, n, d, X)

逆运算:

- findn

- findnz

稠密矩阵恢复:

- full(S)

- issparse

11 线性代数

11.1 矩阵因子化(factorization)

即矩阵分解

- Cholesky

- CholeskyPivoted

- LU

- LUTridiagonal

- UmfpackLU

- QR

- QRCompactWY

- QRPivoted

- Hessenberg

- Eigen: eig, eigvals, eigvecs

- SVD: svd, svdvals

-

GeneralizedSVD

A = [1 2 3; 4 1 6; 7 8 1] trace(A) det(A) inv(A) A = [1.5 2 -4; 3 -1 -6; -10 2.3 4] eigvals(A) eigvecs(A) A = [1.5 2 -4; 3 -1 -6; -10 2.3 4] factorize(A) B = [1.5 2 -4; 2 -1 -3; -4 -3 5] factorize(B) B = [1.5 2 -4; 2 -1 -3; -4 -3 5] sB = Symmetric(B) x = [1; 2; 3] sB\x

11.2 特殊矩阵

- Hermitian: inv, sqrtm, expm

- UpperTriangular: inv, det

- LowerTriangular: inv, det

- Tridiagonal

- SymTridiagonal: eigmax, eigmin

- Bidiagonal

- Diagonal: inv, det, logdet, /

- UniformScaling, 表示一个标量与恒等算子I的乘积: /

12 函数(Function)

函数对象将参数元组映射到返回值。不带括号的函数名表达式指代的是函数对象,可以像值一样进行传递。

12.1 定义

function f(x, y)

x + y

end

f(x, y) = x + y

f(2, 3) # 5

g = f;

g(2, 3) # 5

∑(x, y) = x + y

12.2 return

function g(x, y)

return x * y

x + y

end

12.3 操作符

在Julia中,大多数操作符都是函数

- 除了一些有特殊计算语法的操作符,如&&和||等。这些操作符不能作为函数,因为短路(short-circuit evaluation)计算要求操作数在操作符计算后才被计算

1 + 2 + 3 # infix

+(1, 2, 3)

f = +;

f(1, 2, 3) # not support infix notation

一些特殊操作符

在Base.Operators包中

- hcat(): [A B C …]

- vcat(): [A, B, C, …]

- hvcat(): [A B; C D; …]

- ctranspose(): A’

- transpose(): A.’

- colon(): 1:n

- getindex(): A[i]

- setindex!(): A[i] = x

12.4 匿名函数

() -> 3

x -> x^2 +2x - 1

(x, y, z) -> 2x + y - z

function (x)

x^2 +2x - 1

end

map(round, [1.2, 3.5, 1.7])

map(x -> x^2 + 2x - 1, [1, 3, -1])

12.5 参量

变参(Varargs, 这是”variable number of arguments”的缩写)

bar(a, b, x...) = (a, b, x)

bar(1, 2) # => (1, 2, ())

bar(1, 2, 3) # => (1, 2, (3, ))

bar(1, 2, 3, 4) # => (1, 2, (3, 4))

除了在函数定义中声明集合对象(collection)外,还可以直接在函数调用中手动将集合对象中的元素铰接(splice)到函数参数中;同时,这里对象不需要是元组,函数也不一定是varargs参量形式

x = (3, 4)

bar(1, 2, x...) # => (1, 2, (3, 4))

x = (2, 3, 4)

bar(1, x...) # => (1, 2, (3, 4))

x = (1, 2, 3, 4)

bar(x...) # => (1, 2, (3, 4))

x = [3, 4]

bar(1, 2, x...) # => (1, 2, (3, 4))

baz(a, b) = a + b;

args = [1, 2]

baz(args...) # => 3

可选参量(Optional args)

#interpret a string num as a number in some base

function parse(type, num, base = 10)

###

end

parse(Int, "12", 10) # => 12

parse(Int, "12") # => 12

parse(Int, "12", 3) # => 5

关键字参量(kwargs, “keyword arguments”的缩写)

通过name而非position来识别参量

function plot(x, y; style = "solid", width = 1, color = "black")

###

end

plot(x, y, width = 1)

plot(x, y; width = 1) #equivalent

plot(x, y; (:width, 1)) #equivalent

plot(x, y; :width => 1) #equivalent

function f(; x::Int64 = 1)

###

end

function f(x; y = 0, kwargs...)

###

end

12.6 do语句块

通常做法

map(x->begin

if x < 0 && iseven(x)

return 0

elseif x == 0

return 1

else

return x

end

end,

[A, B, C])

Julia中提供了do保留字,该语法创建的是一个匿名函数,形如do x, do a, b, do(声明() -> …这样的匿名函数)

map([A, B, C]) do x

if x < 0 && iseven(x)

return 0

elseif x == 0

return 1

else

return x

end

end

do语法使得通过函数有效地扩展语言变得更加容易

open("outfile", "w") do io

write(io, data)

end

function open(f::Function, args...)

io = open(args...)

try

f(io)

finally

close(io)

end

end

12.7 dot语法用于函数向量化

任何Julia函数都可以通过dot语法逐元应用到数组或其它集合对象中,这就是广播(broadcast)机制,当然我们也可以通过自定义向量化函数消除dot;Julia中也有嵌套函数实现,只要函数中没有非dot子函数出现,它就可以熔合(fusion)到一起

f.(A)

f(A::AbstractArray) = map(f, A)

f.(args...)

broadcast(f, args...)

f(x, y) = 3x + 4y

f.(pi, A) # => a new array consisting of f(pi, a) for each a in A

f.(vector1, vector2) # => a new vector consisting of f(vector1[i], vector2[i]) for each index i

sin.(cos.(X))

broadcast(x -> sin(cos(x)), X) # equivalent

[sin(cos(x)) for x in X] # equivalent

sin.(sort(cos.(X))) # cannot be merged

当预分配向量化操作的输出数组时,Julia可以实现最大效率。

X .= ...

broadcast!(identity, X, ...) # equivalent

X .= sin.(Y)

broadcast!(sin, X, Y) # overwriting X with sin.(Y) in-place

X[2:end] .= sin.(Y)

broadcast!(sin, view(X, 2:endof(X)), Y)

# In future versions

X .+= Y

X .= X .+ Y # equivalent

X .*= Y

X .= X .* Y # equivalent

13 控制流

13.1 复合(compound)表达式

begin和(;)语句块都没有限定单行还是多行

z = begin

x = 1

y = 2

x + y

end

z = (x = 1; y = 2; x + y)

13.2 条件表达式

if-elseif-else,?:- 不同于C,MATLAB,Perl,Python和Ruby等语言,但是和Java等强类型语言相同的是,在Julia的条件判断中,需要严格定义

Bool类型,而不是任何可以表示true/false的对象,如if 1在Julia中是错误的

13.3 短路(short-circuit)计算

&&, ||

if <cond>

<statement>

end

<cond> && <statement> # equivalent

if ! <cond>

<statement>

end

<cond> || <statement> # equivalent

没有短路的Boolean运算可以通过位运算(&, |)来实现

13.4 重复计算

while, for,break,continue,在for-loop中,索引是局部的,在循环外不可见。

i = 1

while i <= 5

println(i)

i += 1

end

for i = 1:5

println(i)

end

# equivalent

for i in [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

println(i)

end

for i ∈ [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

println(i)

end

# multiple nest

for i = 1:2, j = 3:4

println((i, j))

end

13.5 异常处理

内置异常:下面列出的都是异常类型,加()后表示异常

- ArgumentError

- BoundsError

- CompositeException

- DivideError

- DomainError: sqrt(-1)

- EOFError

- ErrorException

- InexactError

- InitError

- InterruptException

- InvalidStateException

- KeyError

- LoadError

- OutOfMemoryError

- ReadOnlyMemoryError

- RemoteException

- MethodError

- OverflowError

- ParseError

- SystemError

- TypeError

- UndefRefError

- UndefVarError

- UnicodeError

- 自定义异常

type MyCustomException <: Exception

###

end

type MyUndefVarError <: Exception

var::Symbol

end

Base.showerror(io::IO, e::MyUndefVarError) = print(io, e.var, "not defined")

throw()

f(x) = x >=0 ? exp(-x) : throw(DomainError())

typeof(DomainError()) <: Exception # true

typeof(DomainError) <: Exception # false

error()

抛出异常信息,并中断程序运行

info(), warn()

只输出消息,并不中断程序运行

try/catch: catch分句不是必要的

f(x) = try

sqrt(x)

catch

sqrt(complex(x, 0))

end

sqrt_second(x) = try

sqrt(x[2])

catch y

if isa(y, DomainError)

sqrt(complex(x[2], 0))

elseif isa(y, BoundsError)

sqrt(x)

end

end

try bad() catch; x end

# equivalent

try bad()

catch

x

end

rethrow(), backtrace(), catch_backtrace()

finally

13.6 任务(Task, aka Coroutine协程)

任务是一种特殊的控制流特性,它允许计算以某种灵活的方式挂起(suspend)或继续运行(resume)。它还有一些其他的名字,如对称协程(symmetric coroutine), 轻量级线程(lightweight thread), 协作多任务(cooperative multitasking), 单次延续执行流(one-shot continuation)等。

任务同函数调用之间有两点关键的不同之处。一,任务切换不需要任何空间。二,任务间的切换可以任何顺序发生。

function producer()

produce("start")

for n=1:4

produce(2n)

end

produce("stop")

end

p = Task(producer)

consume(p)

for x in Task(producer)

println(x)

end

Task()构造器期望的是一个零参量函数

function mytask(myarg)

###

end

taskHdl = Task(() -> mytask(7)) # need a partial function

# equivalent

taskHdl = @task mytask(7)

核心任务函数

- yieldto(task, value)

- current_task()

- istaskdone()

- istaskstarted()

- task_local_storage()

事件(event)

- wait()

- notify()

- schedule(), @schedule, @async

任务状态

- :runnable

- :waiting

- :queued

- :done

- :failed

Note: 关于Task更多的信息,请阅读Julia并行计算部分。

14 类型系统9

来源于图灵奖得主Dana Scott早期关于Domain Theory的工作。

类型系统通常划分为两种迥然不同的部分,即静态类型和动态类型。在静态类型系统中,程序执行前表达式必须有可计算的类型;而在动态类型中,程序类型判断推迟到运行时完成。通过编写无精确值(这些值在编译时已知)类型的代码,面向对象机制为静态类型语言提供了一些灵活性。编写可以在不同类型上运算的代码的能力称为多态(polymorphism)。经典动态类型语言中的所有代码都是多态的。

Julia类型系统是动态的,但通过指明某些值的特定类型,Julia可以获得静态类型系统的一些好处。这对于生成高效代码是有很大好处的,更重要的是,它允许在函数参量类型上的方法指派(method dispatch)。

Julia中默认值可以是任意类型。

14.1 类型声明

Julia中使用::操作符将类型与程序中的表达式/变量固定在一起,该操作符可以读作”is an instance of”。

(1 + 2) :: AbstractFloat # throw an error

(1 + 2) :: Int # => 3

function foo()

x :: Int8 = 100 # every value assigned to the variable will be converted to the declared type using convert()

x

end

function sinc(x) :: Float64

if x == 0

return 1

end

return sin(pi * x) / (pi * x)

end

14.2 常见类型

抽象类型(abstract types)

抽象类型不能实例化(instantiated),只能作为类型图中的结点。同时抽象类型可以用于类型族的构造。

abstract type <<name>> end

abstract type <<name>> <: <<supertype>> end

上面程序块中的<:读作”is a subtype of”。当不显式给定超类型时,默认超类型是Any。同时,Julia中预定义了抽象的最底层类型,即Union{}。

具体类型(concrete types)

下面讨论的三个类型实际上是相关的,共享了许多性质,它们本质上都是DataType的实例

- 基本原生类型(primitive type)(等同于之前的位类型bits types) 需要注意的是,目前Julia位数只支持8的倍数

primitive type «name» «bits» end

primitive type «name» <: «supertype» «bits» end

primitive type Float16 <: AbstractFloat 16 end

primitive type Float32 <: AbstractFloat 32 end

primitive type Float64 <: AbstractFloat 64 end

primitive type Bool <: Integer 8 end

primitive type Char 32 end

primitive type Int8 <: Signed 8 end

primitive type UInt8 <: Unsigned 8 end

primitive type Int16 <: Signed 16 end

primitive type UInt16 <: Unsigned 16 end

primitive type Int32 <: Signed 32 end

primitive type UInt32 <: Unsigned 32 end

primitive type Int64 <: Signed 64 end

primitive type UInt64 <: Unsigned 64 end

primitive type Int128 <: Signed 128 end

primitive type UInt128 <: Unsigned 128 end

- 组合类型(composite types): record, structure(struct in C), 对象等。

在如Ruby,Smalltalk等纯面向对象语言中,所有值都是对象。在如C++,Java等非纯面向对象语言中,比如整数,浮点数等一些值不被当作对象,而用户定义的组合类型实例被当作真正的对象。

在Julia中,所有值都是对象,但是函数并没有与其作用的对象绑定在一起。因为Julia通过多指派来选择使用函数的某个方法,也就是说一个函数的所有参量类型是在选择方法时确定的。

注意这里Julia引入了struct关键字定义组合类型,当然之前的type还没有取消,仍然可用。不可变的组合类型中也可以包含可变对象,如数组,属性等。不可变类型对象通过拷贝(copying)传递,而可变类型通过引用(reference)传递。在某些情况下不可变类型更高效,更容易推理

struct Foo

bar

baz :: Int

qux :: Float64

end

foo = Foo("Hello, world.", 23, 1.5)

typeof(foo) # => Foo

Foo((), 23.5, 1) # InexactError

当类型像函数一样被应用时,我们称其为构造器(constructor)。Julia自动生成两个构造器,它们被称为默认构造器。

fieldnames(foo)

foo.bar

foo.baz

foo.qux

无属性(field)的组合类型被称为singleton,这样的类型只有一个实例。

struct NoFields

end

is(NoFields(), NoFields()) # => true

NoFields() === NoFields() # => true

is函数用来验证NoFields类型的两个实例是同一个,并且是相同的。

- 可变的组合类型(mutable composite types): 引入mutable struct用于修改实例。

mutable struct Bar

baz

qux :: Float64

end

bar = Bar("Hello", 1.5)

bar.qux = 2.0

bar.baz = 1//2

14.3 类型并(type unions)

IntOrString = Union{Int, AbstractString}

14.4 参数化类型(parametric types)

类型可以带参,因此类型声明实际上引入了整个新类型族。其实有很多语言都支持某种形式的泛化编程。如ML,Haskell,Scala等语言支持真正的带参多态,而如C++,Java等其他语言支持特殊的基于模版(template)的泛化编程。

参数化组合类型

struct Point{T}

x :: T

y :: T

end

Point{Float64}

Point # itself is also a valid type object

Float64Point实例可以紧致高效地表示成64位浮点值对,而RealPoint实例必须要表示成指向单独分配的Real对象的指针对。这种好处可以扩展到数组,浮点数组被存储成64位浮点数的连续内存块,而实数数组必须是指向单独分配的Real对象的指针数组。因为实数实例是任意大小,任意结构的复杂对象。

Point{Float64} <: Point # true

Point{Float64} <: Point{Real} # => false, that is, it is not covariant

function norm{T <: Real}(p :: Point{T})

sqrt(p.x ^ 2 + p.y ^ 2)

end

参数化抽象类型

abstract type Pointy{T} end

Pointy{Float64} <: Pointy

Pointy{1} <: Pointy

struct Point{T} <: Pointy{T}

x :: T

y :: T

end

struct DiagPoint{T} <: Pointy{T}

x :: T

end

abstract type Pointy{T <: Real} end

struct Point{T <: Real} <: Pointy{T}

x :: T

y :: T

end

struct Rational{T <: Integer} <: Real

num :: T

den :: T

end

元组类型

元组类型是协变的,即Tuple{Int}可以是Tuple{Any}的子类型。

struct Tuple2{A, B}

a :: A

b :: B

end

变参元组类型

Vararg{T}, Vararg{T, N}, NTuple{N, T}

isa(("1",), Tuple{AbstractString, Vararg{Int}}) # => true

isa(("1", 1), Tuple{AbstractString, Vararg{Int}}) # => true

isa(("1", 1, 2), Tuple{AbstractString, Vararg{Int}}) # => true

isa(("1",1,2), Tuple{AbstractString, Vararg{Int,2}}) # => true

isa(("1",(1,2)), Tuple{AbstractString, NTuple{2,Int}}) # => true

isa(("1", 1, 2, 3.0), Tuple{AbstractString, Vararg{Int}}) # => false

singleton类型

isa(A, Type{B})为真,当且仅当A和B是相同对象,并且对象为某个类型。Type本身作为抽象类型。

参数化位类型

声明指针类型

primitive type Ptr{T} 64 end

Ptr{Int64} <: Ptr

14.5 类型别名(aliases)

Julia0.6取消了typealias

if Int === Int64

const UInt = UInt64

else

const UInt = UInt32

end

我们可以只简单地限定类型而不限定维数;但是,我们没法等价地只限定维数而不限定元素类型

Array{Float64, 1} <: Array{Float64} <: Array # => true

特别地,我们不能创建关系AA{T} <: AA,因为Array{Array{T, 1}, 1}是一个具体类型。

14.6 常见的类型函数

- isa(value, Type)

- typeof

- supertype

14.7 值类型

Julia不允许在如true/false这样的值上进行指派,但是我们可以在参数化类型上进行指派。

struct Val{T}

end

firstlast(::Type{Val{true}}) = "First"

firstlast(::Type{Val{false}}) = "Last"

firstlast(Val{true}) # => "First"

firstlast(Val{false}) # => "Last"

这里为了Julia一致性,函数参数总是传递Val类型而不是创建一个实例,即foo(Val{:bar})而不是foo(Val{:bar}())。为了防止值类型无用以及性能考虑,我们应该慎用上面的值类型。

14.8 可空类型(nullable types)

Nullable{T}是为了表示缺失值。

x1 = Nullable{Int64}() # a missing value of type T

x2 = Nullable(1) # a non-missing value of type T

isnull(x1) # => true

isnull(x2) # => false

get(x1) # throw NullException

get(x2) # 1

get(x1, 0) # 0

get(x2, 0) # 1

15 方法

方法包含了多态和多指派等概念。比方说,我们有一个函数add,但是两个整数相加和两个浮点数相加是非常不同的,这里就有两个方法,但是Julia中会落入同一个对象,即add函数。对于相同概念的不同实现,我们不需要每次使用都定义,我们只需要对参数类型进行某种组合从而定义函数行为。这样,一个函数的一种可能行为的定义就是一种方法。同时,当应用函数时执行其中一种方法的选择即被称为指派。Julia允许指派基于给定参数的个数和所有参数类型来选择执行哪个方法,这就是多指派。而传统的面向对象语言只允许指派基于第一个参数作出选择。它们之间是有很大不同的。

f(x :: Float64, y :: Float64) = 2 x + y

f(x :: Number, y :: Number) = 2 x - y

f(x, y) = println("Whoa there, Nelly.")

methods(f)

15.1 消除方法歧义

首先定义消除歧义的方法

15.2 带参方法

myappend{T}(v::Vector{T}, x::T) = [v..., x]

# myappend(v::Vector{T}, x::T) where {T} = [v..., x]

mytypeof{T}(x::T) = T # as the return value

same_type_numeric{T<:Number}(x::T, y::T) = true # constrain the type parameter

same_type_numeric(x::Number, y::Number) = false

15.3 带参变参方法

function getindex{T,N}(A::AbstractArray{T,N}, indexes::Vararg{Number,N})

15.4 可选参数

需要注意的是,可选参数与函数绑定,而非与特定方法绑定。它依赖于可选参数的类型。

f(a = 1, b = 2) = a + 2b

# equivalent to the following three methods

f(a, b) = a + 2 b

f(a) = f(a, 2)

f() = f(1, 2) # => 5

# but

f(a::Int, b::Int) = a - 2 b

f() = f(1, 2) # => -3

15.5 关键字参数

这与通常的按位置参数相当不同。关键字参数不参与方法指派。

15.6 函子(functor)

有时也称为可调对象(callable),即将方法添加到类型中从而使得任意Julia对象可调。

构造多项式计算函数

struct Polynomial{R}

coeffs::Vector{R}

end

function (p::Polynomial)(x)

v = p.coeffs[end]

for i = (length(p.coeffs)-1):-1:1

v = v*x + p.coeffs[i]

end

return v

end

p = Polynomial([1,10,100])

p(3)

15.7 空泛化函数

即,没有添加方法的函数。这可以用于将接口定义和接口实现分离。也可以用于文档化以及代码可读性。

function emptyfunc

end

16 构造器

16.1 外部构造器

struct Foo

bar

baz

end

Foo(x) = Foo(x, x)

F() = Foo(0)

16.2 内部构造器

struct OrderdPair

x :: Real

y :: Real

OrderdPair(x, y) = x > y ? error("out of order") : new(x, y)

end

struct T

x :: Int64

# T(x) = new(x) # explicit is equivalent to default constructor

end

自引对象/递归数据结构

为了允许非完全初始化的对象创建,Julia允许调用少于类型属性数目参量的new函数,返回一个未初始化的对象。然后内部构造器方法就可以使用这个非完全(incomplete)的对象,在返回之前完成初始化。

mutable struct SelfReferential

obj::SelfReferential

SelfReferential() = (x = new(); x.obj = x)

end

x = SelfReferential()

is(x, x) # => true

is(x, x.obj) # => true

is(x, x.obj.obj) # => true

16.3 参数化构造器

struct Point{T <: Real}

x::T

y::T

end

Point(1, 2)

Point(1.0, 2.5)

Point{Int64}(1, 2)

Point{Float64}(1.0, 2.5)

Point{Float64}(1, 2) # type promotion, => Point{Float64}(1.0, 2.0)

Point(x::Real, y::Real) = Point(promote(x,y)...) #explicit promotion

16.4 Case study

rational.jl有理数定义和表示,这是一个很好的知识点汇总

struct Rational{T<:Integer} <: Real

num::T

den::T

function Rational(num::T, den::T)

if num == 0 && den == 0

error("invalid rational: 0//0")

end

g = gcd(den, num)

num = div(num, g)

den = div(den, g)

new(num, den)

end

end

Rational{T<:Integer}(n::T, d::T) = Rational{T}(n,d)

Rational(n::Integer, d::Integer) = Rational(promote(n,d)...)

Rational(n::Integer) = Rational(n,one(n))

//(n::Integer, d::Integer) = Rational(n,d)

//(x::Rational, y::Integer) = x.num // (x.den*y)

//(x::Integer, y::Rational) = (x*y.den) // y.num

//(x::Complex, y::Real) = complex(real(x)//y, imag(x)//y)

//(x::Real, y::Complex) = x*y'//real(y*y')

function //(x::Complex, y::Complex)

xy = x*y'

yy = real(y*y')

complex(real(xy)//yy, imag(xy)//yy)

end

(1 + 2im)//(1 - 2im)

convert{T<:Integer}(::Type{Rational{T}}, x::Rational) = Rational(convert(T,x.num),convert(T,x.den))

convert{T<:Integer}(::Type{Rational{T}}, x::Integer) = Rational(convert(T,x), convert(T,1))

function convert{T<:Integer}(::Type{Rational{T}}, x::AbstractFloat, tol::Real)

if isnan(x); return zero(T)//zero(T); end

if isinf(x); return sign(x)//zero(T); end

y=x

a = d = one(T)

b = c = zero(T)

while true

f = convert(T,round(y));y -= f

a, b, c, d = f*a+c, f*b+d, a, b

if y == 0 || abs(a/b-x) <= tol

return a//b

end

y = 1/y

end

end

convert{T<:Integer}(rt::Type{Rational{T}}, x::AbstractFloat) = convert(rt,x,eps(x))

convert{T<:AbstractFloat}(::Type{T}, x::Rational) = convert(T,x.num)/convert(T,x.den)

convert{T<:Integer}(::Type{T}, x::Rational) = div(convert(T,x.num),convert(T,x.den))

promote_rule{T<:Integer}(::Type{Rational{T}}, ::Type{T}) = Rational{T}

promote_rule{T<:Integer,S<:Integer}(::Type{Rational{T}}, ::Type{S}) = Rational{promote_type(T,S)}

promote_rule{T<:Integer,S<:Integer}(::Type{Rational{T}}, ::Type{Rational{S}}) = Rational{promote_type(T,S)}

promote_rule{T<:Integer,S<:AbstractFloat}(::Type{Rational{T}}, ::Type{S}) = promote_type(T,S)

17 接口

Julia很多强大的能力和扩展性都来源于非正式的接口集。

17.1 迭代

- start(iter)

- next(iter, state)

- done(iter, state)

- length(iter)

- eltype(IterType)

- size(iter, [dim…])

for i in iter # or "for i = iter"

# body

end

# equivalent

state = start(iter)

while !done(iter, state)

(i, state) = next(iter, state)

# body

end

平方数迭代序列,in,mean,std,collect等函数也可以作用在这种序列上

struct Squares

count::Int

end

Base.start(::Squares) = 1

Base.next(S::Squares, state) = (state*state, state+1)

Base.done(S::Squares, state) = state > S.count; Base.eltype(::Type{Squares}) = Int # Note that this is defined for the type

Base.length(S::Squares) = S.count;

for i in Squares(7)

println(i)

end

Base.sum(S::Squares) = (n = S.count; return n*(n+1)*(2n+1)÷6)

sum(Squares(1803))

17.2 索引

- getindex(X, i):X[i]

- setindex!(X, v, i):X[i] = v

- endof(X):X[end]

function Base.getindex(S::Squares, i::Int)

1 <= i <= S.count || throw(BoundsError(S, i))

return i*i

end

Squares(100)[23]

Base.endof(S::Squares) = length(S)

Squares(23)[end]

Base.getindex(S::Squares, i::Number) = S[convert(Int, i)] Base.getindex(S::Squares, I) = [S[i] for i in I]

Squares(10)[[3,4.,5]]

18 模块

Julia模块是单独的变量工作空间。模块使得我们可以创建一些顶层设计而不用担心和其他模块发生命名冲突。

- 模块体不缩进,因为缩进会导致整个文件缩进

- using Lib语句表示当程序遇到在当前模块中没有定义的全局变量时,系统会搜索所有Lib包对外开放的变量

- using BigLib: thing1, thing2是using BigLib.thing1, using BigLib.thing2的缩写

- import语法和using相同,只是一次只能作用一个名字

- importall等同于将import作用在特定模块的所有名字上

- 变量通过import或using引入后,模块不能再创建同名的变量;被引入的变量将成为只读变量

module MyModule

using Lib

using BigLib: thing1, thing2

import Base.show

importall OtherLib

export MyType, foo

struct MyType

x

end

bar(x) = 2x

foo(a::MyType) = b(a.x) + 1

show(io::IO, a::MyType) = print(io, "MyType $(a.x)")

end

18.1 标准模块

- Main:在提示符窗口中的变量存在Main中,用

whos()函数查看 - Core:包含所有内置标识符,所有模块隐式地using Core

- Base:标准库,所有模块隐式地using Base

18.2 eval

模块自动包含了eval函数的定义;如果不想要默认定义,我们可以使用关键字baremodule代替module,但是我们注意到Core库仍然隐式地被引入

baremodule Mod

using Base

eval(x) = Core.eval(Mod, x)

eval(m, x) = Core.eval(m, x)

###

end

18.3 模块路径

当给定using Foo时,系统开始在Main内搜索Foo,当Main中不存在Foo模块时,系统设法require("Foo"),这会导致系统从已安装包中加载代码

绝对路径

using Base.Sort

相对路径

module Parent

module Utils

###

end

using .Utils

###

end

相当路径使用.Utils符号来作用,甚至我们可以使用..Utils来寻找包含Parent的模块中的Utils而非在Parent本身当中寻找

18.4 LOAD_PATH

全局变量,包含了当调用require时Julia搜索模块的目录;使用push!来扩展文件路径

push!(LOAD_PATH, "/Path/To/My/Module/")

将该语句放入文件~/.juliarc.jl中,我们可以在每次Julia启动时扩展LOAD_PATH。当然我们还可以定义环境变量JULIA_LOAD_PATH来扩展模块加载路径

18.5 其它

- import/export宏: import Mod.@mac

- 其它模块中宏调用: Mod.@mac / @Mod.mac

- M.x = y不起作用,因为全局赋值是局限在模块内的

18.6 模块初始化、预编译

初始化

__init__()

预编译

加载大模块通常需要花费几分钟时间,因此Julia提供了预编译模块的创建来减少加载时间。Julia中有两种机制来实现预编译模块:

- 增量编译incremental compile:在模块文件顶部(即module开始前)添加__precompile__(),同时我们也可以手动调用Base.compilecache(modulename),调用__precompile__(false)关闭预编译,通常情况下为了安全考虑,我们都需要关闭预编译功能

- 通常的系统镜像custom system image:在启动Julia时使用-J选项

19 文档(documentation)

文档系统内置在Julia0.4往后版本,而Julia0.3中是通过Docile.jl包来实现的。

19.1 docstrings

"Tell whether there are too foo items in the array."

foo(xs::Array) = ###

19.2 使用规则

文档被解释成Markdown

下面块中数字1后面的```应该写在下一行,这里只是为了文章前后输出一致

"""

bar(x[, y])

Compute the Bar index between `x` and `y`. If `y` is missing, compute the Bar index between all pairs of columns of `x`.

# Examples

```julia

julia> bar([1, 2], [1, 2])

1```

"""

function bar(x, y) ###

- 在文档顶部总是展示函数标识,并以四空格方式缩进,使得能够以Julia代码方式输出

- 包含单行语句描述函数功能:不要以第三人称方式描述,以英文句号结束

- 不要在描述语句中重复强调

the function或者参量类型 - 仅仅对于复杂函数参量,提供参量列表

"""

###

# Arguments

* `n::Integer`: the number of elements to compute.

* `dim::Integer=1`: the dimensions along which to perform the computation.

###

"""

# Examples段落下的事例应该用```julia块包裹,这可以用于程序运行结果与文档中给定结果的比较检测

"""

Some nice documentation here.

```jldoctest

julia> a = [1 2; 3 4]

2×2 Array{Int64,2}:

1 2

3 4 ```

"""

- 使重音符`来标识代码和方程,并且使用Unicode字符而非转义字符:

``α = 1`` - 文档开始和文档结束```单独成行

19.3 文档访问

- REPL或者IJulia中使用?

- Juno中使用Ctrl-D

19.4 函数&方法

一般只有泛化方法或者函数本身可以文档化。特定方法只有在和其他更泛化的方法极其不同时才文档化。

19.5 @doc

for (f, op) in ((:add, :+), (:subtract, :-), (:multiply, :*), (:divide, :/))

@eval begin

$f(a,b) = $op(a,b)

end

end

@doc "`add(a,b)` adds `a` and `b` together" add

@doc "`subtract(a,b)` subtracts `b` from `a`" subtract

在非顶层块(如if,for,let)中写的文档不会自动添加到文档系统中,必须使用@doc。

if VERSION > v"0.4"

@doc "###" ->

f(x) = x

end

19.6 @__doc__

如果宏返回包含多个子表达式的语句块,那么应该被文档化的子表达式必须使用@__doc__来标记

macro example(f)

quote

$(f)() = 0

@__doc__ $(f)(x) = 1

$(f)(x, y) = 2

end |> esc

end

20 元编程(metaprogramming)

Julia语言像Lisp一样将代码表示成语言本身的一个数据结构。因为代码被表示成可以在语言内创建和操纵的对象,所以程序可以变换和生成自己的代码。这使得不需要额外的构建(build)步骤就可以成熟地进行代码生成(code generation),同时也使得类Lisp宏可以操纵在抽象语法树(abstract syntax tree, AST)上

20.1 :操作符

- 表示Symbol

:foo == Symbol("foo")

- 表示Expr

ex = :(a + b * c + 1)

20.2 程序表示

prog = "1 + 1"

ex1 = parse(prog)

typeof(ex1) # => Expr

ex1.head

ex1.args

ex1.typ

ex2 = Expr(:call, :+, 1, 1)

# equivalent

ex1 == ex2 # true

dump(ex2) # display of Expr objects

ex3 = parse("(4 + 4) / 2") # nested

Meta.show_sexpr(ex3) #another way to view expression

ex = quote

x = 1

y = 2

x + y

end

20.3 插值

a = 1

ex1 = :($a + b)

ex2 = :(a in $:(1, 2, 3))

ex3 = :(:a in $(:(:a + :b)))

20.4 eval()

20.5 表达式上的函数

function math_expr(op, op1, op2)

expr = Expr(:call, op, op1, op2)

return expr

end

ex = math_expr(:+, 1, Expr(:call, :*, 4, 5))

eval(ex)

20.6 宏

宏将参量元组映射到被返回的表达式,相应的表达式直接编译而不是通过运行时eval调用。

macro sayhello(name)

return :(println("Hello, ", $name, "!"))

end

@sayhello("world") # => Hello, world!

ex = macroexpand(:(@sayhello("world"))) # extremely useful for debugging macros

宏是必要的:当代码被解析时执行宏,因此宏允许在整个程序运行前生成和包含定制代码片段。

macro twostep(arg)

println("I execute at parse time. The argument is: ", arg)

return :(println("I execute at runtime. The argument is: ", $arg))

end

ex = macroexpand(:(@twostep :(1, 2, 3)))

typeof(ex)

ex

eval(ex)

调用宏

@name expr1 expr2 ...

@name(expr1, expr2, ...)

@name (expr1, expr2, ...) # a tuple as one argument

macro showarg(x)

show(x)

###

end

@showarg(a)

@showarg(1+1)

@showarg(println("Yo!"))

高级宏

macro assert(ex, msgs...)

msg_body = isempty(msgs) ? ex : msgs[1]

msg = string(msg_body)

return :( $ex ? nothing : throw(AssertionError($msg)))

end

macroexpand(:(@assert a==b))

macroexpand(:(@assert a==b "a should equal b!"))

esc()

20.7 代码生成

for op = (:+, :*, :&, :|, :⊻)

eval(quote

($op)(a,b,c) = ($op)(($op)(a,b),c)

end)

end

# equivalent

for op = (:+, :*, :&, :|, :⊻)

eval(:(($op)(a,b,c) = ($op)(($op)(a,b),c)))

end

for op = (:+, :*, :&, :|, :⊻)

@eval ($op)(a,b,c) = ($op)(($op)(a,b),c)

end

对于更大的代码块:

@eval begin

# multiple lines

end

20.8 @generated

# runtime loop

function sub2ind_loop{N}(dims::NTuple{N}, I::Integer...)

ind = I[N] - 1

for i = N-1:-1:1

ind = I[i]-1 + dims[i]*ind

end

return ind + 1

end

# recursion

sub2ind_rec(dims::Tuple{}) = 1

sub2ind_rec(dims::Tuple{},i1::Integer, I::Integer...) = i1==1 ? sub2ind_rec(dims,I...) : throw(BoundsError())

sub2ind_rec(dims::Tuple{Integer,Vararg{Integer}}, i1::Integer) = i1

sub2ind_rec(dims::Tuple{Integer,Vararg{Integer}}, i1::Integer, I::Integer...) = i1 + dims[1]*(sub2ind_rec(tail(dims),I...)-1)

# compile-time iteration

@generated function sub2ind_gen{N}(dims::NTuple{N}, I::Integer...)

ex = :(I[$N] - 1)

for i = N-1:-1:1

ex = :(I[$i] - 1 + dims[$i]*$ex)

end

return :($ex + 1)

end

21 包(package, Pkg)

21.1 包管理

官方的Julia包注册在METADATA.jl文件库中

- Pkg.init()

- Pkg.status()

- Pkg.installed()

- pkg.add()

-

Pkg.resolve()/Pkg.edit()

julia> echo UTF16 >> ~/.julia/v6.0/REQUIRE julia> Pkg.resolve() # equivalent, except that Pkg.add() doesn’t change REQUIRE until after installation has completed Pkg.add("UTF16") - Pkg.rm()

-

Pkg.setprotocol!()

git config --global url."https://".insteadOf git:// - Pkg.dir(): 离线安装

- Pkg.build()

- Pkg.test()

- Pkg.clone(url): 对于官方未注册的包

- Pkg.update()

- Pkg.checkout()

- Pkg.free()

- Pkg.pin()

21.2 包开发

初始设置

git config --global github.user "USERNAME"

git config --global user.name "FULL NAME"

git config --global user.email "EMAIL"

Pkg.add("PkgDev")

import PkgDev

对已存在的包进行修改

- 文档修改: README.md

-

代码修改

Pkg.checkout("Images") # check out the master branch <here, make sure your bug is still a bug and hasn't been fixed already> cd(Pkg.dir("Images")) ;git checkout -b myfixes <edit code> Pkg.test("Images") ;git commit -a -m "Fix foo by calling bar" # write a descriptive message using PkgDev PkgDev.submit("Images") -

细节描述

cd(Pkg.dir("Foo")) # go to Foo's folder ;git command arguments... # command will apply to FooPkgDev.submit("Foo")git push git diff git reset --hard origin/master git rebase -i origin/master git remote add myfork https://github.com/myaccount/Foo.jl.git git push myfork +fixbar

创建新包

REQUIRE中添加julia 0.x 0.y-

命名规则

- 避免行话/术语:USA(good), PMA(bad, even if you know about positive mental attitude)

- 避免在包名中出现

Julia - 提供与一个新类型相关的很多功能的包应该以复数形式命名: DataFrames, BloomFilters, SortingAlgorithms, JuliaParser

- 清晰命名: RandomMatrices(good), RndMat(bad), RMT(bad)

- 不太系统化的名字适合用于仅仅实现某一个方式的包: Gadfly, PyPlot, Winston

- 外部库封装: CPLEX.jl, MATLAB.jl

生成包

pkgDev.generate("FooBar", "MIT")

;cd ~/.julia/v0.6/FooBar && git show --stat

PkgDev.register("FooBar")

;cd ~/.julia/v0.6/METADATA && git show

PkgDev.publish()

PkgDev.tag("FooBar")

;cd ~/.julia/v0.6/FooBar && git tag

修改包需求

cd ~/.julia/v0.6/METADATA/FooBar/versions/0.0.1 && cat requires

vi requires

22 编码风格

22.1 编写函数而不仅仅只是写脚本

- 可重用

- 可测试

22.2 避免类型过于详细

convert(Complex{Float64}, x) # bad

complex(float(x))

addone(x) = x + one(x)

22.3 处理调用函数中多余参量的多样性

function foo(x::Int, y::Int)

...

end

foo(Int(x), Int(y))

这里的foo函数只处理整型值,调用者需要手动考虑任意输入参量的类型转换。这对于函数的干净整洁是有很大好处的。正像很多优秀的机器学习库,并没有过度提供数据预处理,缺失值处理等琐碎问题,好的库应该只关心核心功能本身,而将其它剥离出系统外,由用户或第三方功能库处理。

22.4 使用!

- sort!

- push!

- pop!

- splice!

function double!{T<:Number}(a::AbstractArray{T})

for i = 1:endof(a); a[i] *= 2; end

a

end

22.5 避免奇怪的类型并

如Union{Function, AbstractString}

22.6 避免在属性(field)中使用类型并

mutable struct MyType

...

x :: Union{Void, T}

end

22.7 避免过于精细的容器类型

a = Array{Union{Int,AbstractString,Tuple,Array}}(n) # bad

a = Array{Any}(n)

22.8 使用同base/一致的命名习惯

22.9 不要滥用try-catch

22.10 不要将条件括起来

if a == b

22.11 不要滥用...

[a..., b...] # bad

[a; b]

[a...] # bad

collect(a)

22.12 不要使用没必要的静态参数

foo(x :: T)where {T <: Real} = ... # bad

foo(x::Real) = ...

22.13 避免实例和类型混淆

推荐默认使用实例,但是枚举类型除外

22.14 不要滥用宏

22.15 不要在接口层暴露不安全操作

mutable struct NativeType

p::Ptr{UInt8}

...

end

getindex(x::NativeType, i) = unsafe_load(x.p, i)

22.16 避免重载基本库容器类型的方法

show(io::IO, v::Vector{MyType}) = ...

22.17 小心对待类型相等

- isa()

- issubtype():

<: - ==一般只用于比较具体类型,如

T == Float64

22.18 不要写x->f(x)

map(x -> f(x), a) # bad

map(f, a)

22.19 避免在通用代码中的数值使用浮点数

尽可能使用在类型提升中对参量影响很小的数值类型

f(x) = 2.0 * x

f(1//2)

f(1/2)

f(1)

g(x) = 2 * x

g(1//2)

g(1/2)

g(2)

h(x) = 2//1 * x

h(1//2)

h(1/2)

h(1)

23 FAQ

23.1 会话&REPL

-

我如何删除内存中的对象?

Julia中没有类似Matlab中

clear一样的函数。在Julia会话中一旦命名变量,那么它将一直存在。如果担心变量对内存的占用,你可以在变量不再使用时,释放内存A = 0,垃圾回收器下次运行时就会释放内存,或者调用gc()强制执行。 -

我如何修改类型/immutable的声明

Main模块中的类型不能重新定义,但是我们可以重新定义模块

include("mynewcode.jl") # this defines a module MyModule obj1 = MyModule.ObjConstructor(a, b) obj2 = MyModule.somefunction(obj1) # Got an error. Change something in "mynewcode.jl" include("mynewcode.jl") # reload the module obj1 = MyModule.ObjConstructor(a, b) # old objects are no longer valid, must reconstruct obj2 = MyModule.somefunction(obj1) # this time it worked! obj3 = MyModule.someotherfunction(obj2, c) ...

23.2 函数

-

为什么我将参量x传给函数,并在函数内修改,但是在函数外x并没有改变?

Julia中将变量x作为参量传递给函数并不能改变对x的绑定;但是如果x是Array类型或任意其它可变类型,那么我们虽然不能解除Array对x的绑定,但是可以改变它的内容。

x = 10 function change_value!(y) y = 17 end change_value!(x) # 17 x # 10x = [1, 2, 3] function change_array!(A) A[1] = 5 end change_array!(x) # 5 x # [5, 2, 3] -

我能在函数内使用using或import吗?

不能。你可以在函数外使用,或者将调用模块和函数封装在一个新的模块中。

-

···算符能做什么?

Julia新手容易对此产生混淆。根据上下文不同,它可以分为两种用处。

第一种,用于在函数定义中将多个参量组合成一个参量

function printargs(args...) @printf("%s\n", typeof(args)) for (i, arg) in enumerate(args) @printf("Arg %d = %s\n", i, arg) end end printargs(1, 2, 3)第二种,用于在函数调用种将一个参量分成多个不同参量

function threeargs(a, b, c) @printf("a = %s::%s\n", a, typeof(a)) @printf("b = %s::%s\n", b, typeof(b)) @printf("c = %s::%s\n", c, typeof(c)) end vec = [1, 2, 3] threeargs(vec...)

23.3 类型,类型声明&构造器

-

什么叫类型稳定?

它是说输出类型可以通过输入类型来预测。并且,输出类型不依赖于输入值发生变化。

function unstable(flag::Bool) if flag return 1 else return 1.0 end end -

对于某些表面上看明智的操作为什么Julia会给出DomainError?

为了保证类型稳定。对于sqrt(2.0)它会返回一个浮点数,但是sqrt(-2.0)如果返回复数,就会导致类型不稳定,因此需要传入复数。2^-5道理相同。

sqrt(-2.0) 2^-5 sqrt(-2.0 + 0im) 2.0^-5 -

为什么Julia使用原生(native)机器整数算术?

这意味着Int值范围是有界的。

typemax(Int) ans + 1 -ans 2 * ansMatlab对于下面处理是错误的。

julia> n = 2^62 julia> (n + 2n) >>> 1

23.4 包&模块

-

using和importall之间的差别是什么?

它们之间只有一个差别。使用using,你需要使用一个新的方法

function Foo.bar(..来扩展模块Foo的函数bar;但是使用importall或import Foo.bar,你只需要使用function bar(...,它会自动扩展模块Foo的函数bar。

23.5 nothing&缺失值

-

null或nothing在Julia中如何工作?Julia中并没有空值。当引用未初始化时,对它的访问将立即造成异常的抛出。者可以使用

isdefined函数检测。nothing仅仅只是Void类型的singleton对象。空元组()是nothing的另一种形式,通常它被当作零个值的元组而非nothing。在Julia0.4之前版本中,我们还能看到None,它是空类型(或称为底类型)。现在版本中,使用Union{}来代替表示。有时候有些统计数据会缺失,所以最好使用

Nullable{T}类型

23.6 内存

-

当x和y是数组时,为什么x += y会分配内存?

在Julia解析过程中,用x = x + y来代替x += y。对于数组而言,它没有将结果存在与x相同的位置,而是分配一个新的数组来存储结果。对于不可变类型,它没有改变值本身,只是改变对变量的绑定,因此改变不可变类型值的唯一方法就是重新赋值。

function power_by_squaring(x, n::Int) ispow2(n) || error("This implementation only works for powers of 2") while n >= 2 x *= x n >>= 1 end x end

23.7 异步I/O&并发同步写

-

为什么对相同流的并发写操作会导致内部混合的(inter-mixed)输出呢?

@sync for i in 1:3 @async write(STDOUT, string(i), " Foo ", " Bar ") endprint和println在函数调用期间会将数据流锁住。

@sync for i in 1:3 @async println(STDOUT, string(i), " Foo ", " Bar ") end或者通过锁机制实现

l = ReentrantLock() @sync for i in 1:3 @async begin lock(l) try write(STDOUT, string(i), " Foo ", " Bar ") finally unlock(l) end end end

24 与其它语言间的差异

24.1 与MATLAB的差异

- 方括号索引: A[i, j]

- 数组引用赋值: A = B

- 值也是引用传递和赋值的

- Julia不会自动增加数组大小: push!(), append!()

- 虚部单位im: sqrt(-1)

- 多个值可以作为元组返回和赋值: (a, b) = (1, 2), a, b = 1, 2

- [x, y, z], [x y z], [a b; c d], [x; [y, z]]

- Range对象:a:b, a:b:c, 为了构造向量,collect(a:b);linspace()

- Julia函数从最后一个表达式中返回值,也可以用return关键字

- 当通过单参数调用时,sum(), prod(), max()等约化方法在数组的每个元素上进行,即使数组是多维的

- sort()等函数默认是列优先的,sort(A)等价于sort(A, 1)。对于1xN数组,使用sort(A)返回的是没有修改的参量A,正确用法是sort(A, 2)

- 如果A是2维数组,那么fft(A计算的是2D FFT;但是fft(A, 1)计算的是列优先的1D FFT

- 零参量函数调用也必须加()

- 不鼓励在语句末尾使用;

- 如果A和B是数组,那么A==B等比较不会返回布尔数组,相应地我们应该使用A .==B

- &, |和⊻等价于Matlab中的and, or和xor

- svd()返回的是奇异值向量而不是稠密对角阵

- Julia中不使用…来表示代码行的继续,对于不完整表达式Julia会自动连接到下一行

- 不同于Matlab,在非交互式环境中,Julia不能设置ans

- 不同于Matlab的class,Julia类型不支持运行时动态添加属性。代替地可以使用Dict

- Matlab只有一个全局作用域,而Julia每个模块都有一个自己的全局作用域/命名空间

- Matlab中移除不要的值使用逻辑索引,如x(x>3), x(x>3) = []; 而在Julia中提供了多种方式,如x[x.>3], x = x[x.>3]; filter(z->z>3, x), filter!(z->z>3, x)

- Matlab中抽取数组所有元素使用vertcat(A{:}); Julia中使用vcat(A…)

24.2 与R的差异

- Julia单引号包裹字符,而非字符串

- Julia可以通过字符串索引(即切片)来创建子字符串,但是R必须先转换成字符向量

- 多行字符串使用”"”…”"”表示

- Julia中使用mod(a, b)表示取模,a % b表示余数,但是R中使用%%

- Julia中逻辑索引必须与向量等长,否则会抛出BoundError: [1, 2, 3, 4][[true, false, true, false]]

- Julia不总是允许不同长度的向量之间的运算

- Julia中的apply()函数首先取函数,其次取参量,不同于R中的lapply()

- Julia中使用end表示语句块的结束,对于单行条件语句,如

if (cond) statement,有三种表达,if cond; statement; end,cond && statement和!cond || statement - Julia中的

<-,<<-和->不是赋值算子 - 使用[]构造向量,如[1, 2, 3]等价于R中的c(1, 2, 3)

- Julia中的

*可以进行矩阵乘法,如A * B等价于R中的A %*% B, 而R中的*进行的是按元乘法,即Hadamard乘法。 - 注意: Julia中矩阵转置使用

.'(transpose()),而共轭转置使用'(ctranspose()),如A.'等价于R中的t(A) - Julia中并没有将0,1作为布尔值,相应地我们需要

if true,if Bool(1)或if 1==1 - Julia不支持nrow和ncol函数,对应地,size(M, 1), size(M, 2)

- R中1和c(1)是相同的。但是Julia严格区分标量,向量和矩阵。对于向量x和y,x’ * y结果是一个单元素向量,而dot(x, y)结果是标量

- diag(), diagm()

- Julia不能将结果赋值给一个函数调用: 如我们不能做下面操作

diag(M) = ones(n) - Julia不鼓励将函数都放在主命名空间中。很多统计相关的功能可以在JuliaStats组织下的包中找到。如Distributions包提供了与概率分布有关的函数,DataFrames包提供了data frames,GLM包提供了泛化线性模型

- Julia提供了元组和实hash table。Julia0.6版本中取消了list, 当返回多项时,使用如(1, 2)这样的元组

- 鼓励写自己的类型

- Julia采用引用传递

- Julia向量和矩阵采用hcat(), vcat()和hvcat()连接,而R中采用c, rbind和cbind

- Julia中像a:b这样的形式不是向量的简写,它们只是特定的Range,用于迭代,好处是只有很低的内存负载。可以使用collect(a:b)转换成向量

- max()和min()等价于R中的pmax和pmin。maximum()和minimum()代替了R中的max和min

- Julia中, A=[[1 2], [3 4]]; sum(A); sum(A, 1); sum(A, 2); sum(A, [1, 2]) = 10。R中, B = rbind(c(1, 2); c(3, 4)); sum(B, 1) = 11; sum(B, 2) = 12

- R中的性能提升需要通过向量化来实现;而Julia中几乎是相反的。

- 不支持类R的惰性计算

- 不支持NULL类型

- 没有R中的assign和get

- return 不需要括号

24.3 与Python的差异

- Julia中如果没有详述显式元素类型,由向量组成的向量会自动连接成一维向量: 如[1, [2, 3]] => [1, 2, 3]; Int[1, Int[2, 3]]将抛出异常; Any[1, [2,3]]不自动连接; Vector{Int}[[1, 2], [3, 4]]不自动连接,类似于Python中列表的列表,这不同于整型数组

- Julia中没有pass关键字

- Julia索引从1开始,Python索引从0开始

- Julia切片包含最后一个元素, 如Julia中的a[2:3]等价于Python中的a[1:3]

- Julia不支持负索引,列表或数组最后一个元素用end索引,而Python中用-1索引

- Julia中的列表推导不支持可选的if分句

- Julia中语句结束用end,Python需要严格的缩进

- Julia数组列优先(Fortran序),而Numpy是行优先的(C序)

- +=,-=等更新算子不是本地改变的,需要重新分配内存空间,这不同于Numpy。如A = ones(4); B = A; B += 3不改变A中的值。如果需要精确的改变方式,使用B[:] += 3或InplaceOps.jl包

- 每次方法调用时Julia都计算函数参量的默认值;而Python只在函数定义时计算一次。如f(x = rand()) = x每次无参调用时都返回一个新的随机数, g(x = [1, 2]) = push!(x, 3)每次无参调用g()时都返回[1, 2, 3]

24.4 与C/C++的差异

- Julia中需要小心对待空格

- Julia中,无小数点的数字直接创建的是Int类型的有符号整型,如果太大会采用晋升机制

- Julia中用//表示有理数,#表示注释,而在C/C++中//表示注释

- #=表示多行注释的开始,#=结束注释

- 多值返回,Julia中

(a, b) = myfunc(),a, b = myfunc();但是C/C++中,必须把指针传递给值,a = myfunc(&b) - Julia中用⊻表示按位异或操作,而C/C++中使用\^

- Julia中\^表示指数运算,即pow

- >>表示算术移位,>>>表示逻辑移位;而C/C++中>>操作依赖于值的类型

- ->在Julia中创建匿名函数,而C/C++中表示通过指针访问对象成员

- Julia宏作用在解析表达式上,而非程序文本上

- C++中默认采用静态指派。如果需要动态指派,我们需要声明函数为virtual虚函数(方法在this上指派);另一方面,Julia中每个方法都是”virtual”(在每个参量类型上指派)。

-

VB Shah, A Edelman, S Karpinski and J Bezanson. Novel algebras for advanced analytics in Julia. High PERFORMANCE Extreme Computing Conference, IEEE, pp.1-4(2013). ↩

-

Avik Sengupta. Julia High Performance, 2016. ↩

-

J. Bezanson, A. Edelman, S. Karpinski, et al. Julia: A Fresh Approach to Numerical Computing. Eprint Arxiv, 2014. ↩

-

Anshul Joshi. Julia for Data Science, 2016. ↩

-

Alexander Chen, Alan Edelman, Jeremy Kepner, Vijay Gadepally, Dylan Hutchison. Julia Implementation of the Dynamic Distributed Dimensional Data Model, High Performance Extreme Computing Conference, 2016:1-7. ↩

-

Ivo Balbaert. Getting Started with Julia Programming, 2015. ↩

-

Malcolm Sherrington. Mastering Julia, 2015. ↩

-

Jeff Bezanson, Stefan Karpinski, Viral Shah, Alan Edelman, et al., Julia Language Documentation(Release 0.6.0-dev). ↩

-

Jeff Werner Bezanson. Abstraction in Technical Computing(PhD Thesis), 2015. ↩